(Apparently I don’t put enough practical information on my blog, so here goes…)Many aspiring picture book writers start off in rhyme. It’s easy peasy and kids love it, right? Well, slushpile veterans can reel off numberless examples of second-rate verse and failed Dr Seuss-a-likes, so let’s start with this crucial fact: IT’S MUCH HARDER THAN YOU THINK!‘ Easy’ rhymes with ‘cheesy’, after all.

(Apparently I don’t put enough practical information on my blog, so here goes…)Many aspiring picture book writers start off in rhyme. It’s easy peasy and kids love it, right? Well, slushpile veterans can reel off numberless examples of second-rate verse and failed Dr Seuss-a-likes, so let’s start with this crucial fact: IT’S MUCH HARDER THAN YOU THINK!‘ Easy’ rhymes with ‘cheesy’, after all.

Part of the nature of good rhyming texts is that they are a joy to read and roll off the tongue, but that does NOT mean they slide off the ballpoint without hours of sweat and stress. The English Language may be rich in words, shades of meaning and overall loveliness, but it’s comparatively poor when it comes to rhyme, especially true rhymes. Here are some technical points and tips that are worth keeping in mind:

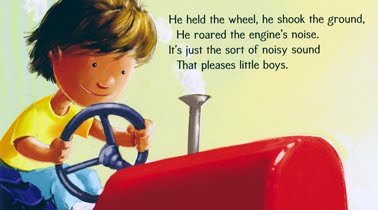

1. True rhymes are best because they are the easiest to read and clearest for children. But they are very difficult to keep up. A rhyme is true if it rhymes on the last stressed syllable, with all subsequent unstressed syllables being identical. For example: HAIR-i-ness and SCAR-i-ness. Some words have large numbers of true rhymes (‘-IGHT’ words, for example) but most will have very few, and given the restricted vocabulary of writing for the very young, this fact makes rhyming in picture books a real challenge. The clever way round this, and the most fun, is to seek out near-true rhymes (NOR-wich and PORR-idge). The very worst thing you can do is fall back on forced rhymes.

2. Alliteration is more than just using words that start with the same letter. It’s about unifying a line and creating points of contact between lines. It only works with stressed syllables (the lurid allure of London), regardless of whether or not they begin a word, and is all too easy to overdo. It’s much better to have just two alliterated syllables in a line than to try and squeeze in as many as possible. And don’t forget, a Big Brown Bear is also a Big Fat Cliché.

3. Don’t forget assonance! The overlooked but secretly rather wonderful cousin of alliteration, assonance is rhyme in stressed vowel sounds, and a subtle way to unify a line (his little sister’s slipper). To be used sparingly but cleverly.

4. Metre and syllable count ARE important. Forced scansion is just as bad as forced rhyme, since it can cause a reader to stumble. The whole point of metre is to make the verse predictable. Any ambiguity in either rhyme or scansion is likely to wreck your text, because…

5. …picture book readers are usually not children at all, but ADULTS. This is important because sadly many parents are reluctant to read to their children even at the best of times. But at the end of the day, after work and a long commute followed by screaming fits over broccoli, even reading a short bedtime story can seem onerous. You will win friends amongst parents if you give them something effortless to read and you will make the children smile if you give them vivid rhymes they can shout out and a rhythm they can anticipate. Add a dollop of fun and you’re done!

Next post: a publisher’s perspective. In the meantime, my latest picture book in rhyme is available everywhere and would make a great gift when you’ve finished dissecting it.

This is brilliant – and not just for writers of children's picture books! Could you have an "ask the writer/illustrator" blog post, too?

Thanks, Rachel.Would an 'ask the writer/illustrator' post involve me sitting in state while the people come into the presence? I'd like that:) Seriously though, do you mean inviting questions in the comments? But what if no one asked anything? I'd be Tommy No-Mates again.

HA! I meant just drop a Q in the comments. I could assume multiple IDs and ask loads! (Given myself an idea for my blog now…:)

Wonderful post, Thomas, and all great advice. I've noticed, when reading such books to my own children, how much more I enjoy reading them when they have a proper rhythm and rhyme structure. And also how they grate when lines don't fit etc.

Thanks, Simon — I'm glad you agree. I learnt all this the hard way.

I love the post very much because I'm translating a poem.Thank you for this wonderful post.Sandra

I’m writing to tell you about Fabella, the site for unpublished childrens’ picture books.

http://www.fabella.co.uk

Fabella is the next best thing to getting a book published – it selects the very best picture stories and illustrations and then showcases them for the world (and publishers) to see. Work can be shared, liked on Facebook and readers can review stories and post comments.

It is also a platform for writers to find illustrators and vice versa.

Fabella is unique as it is the only site specialising in childrens’ picture stories and which is selective in the work it features.

I hope you find it interesting and perhaps you could share the site with your readers as it is an alternative avenue to self publishing.

Best wishes

Tori

Hi Tori! I just found Thomas Taylors blog and his posts about writing children’s books that rhyme. I tried to go to the fabella site you mentioned (I’m in the U.S.) and couldn’t access it. Has it changed names or addresses since your post? Thanks! Ann

Thank you for saying that it’s ok to have near rhymes. I worked with Personal Assistant who wanted my rhymes to be exact and I complied, but I typically write near rhymes. That’s not to say that all of them should be near-rhymes, I know. Great advice! I love your blog.

My Dad was an expert. I grew up with his rhymes that “rolled of his tongue” and now I am attempting the same after collaborating with him on the book,

‘Into the Woods for a Basket of Soup”. I would love to hear your thoughts about this book and the follow-up; ‘How the Fox Got His Socks’

Thank you.